Interview: Thirty Odd Minutes With Stewart O'Nan

Interview by Eric Sandberg

At fifty-eight years young, Stewart O'Nan has seen seventeen of his works of fiction published along with two non-fiction books, one of which is Faithful [with Stephen King] a best-selling bleachers-eye-view of the first championship season for the Boston Red Sox since Babe Ruth was traded. All of this since he, with the full support of his saintly wife, Trudy, abandoned his career as an Aerospace engineer to earn his MFA, ultimately publishing his first collection of short stories In The Walled City [Drew Heinz Literary Prize for Literature] in 1993.

His first novel Snow Angels was adapted as a film and at least two other novels are in pre-production with names like Tom Hanks and Emily Watson being bandied about. Early in his career, Granta named him one of America's best young novelists.

Stewart O'Nan and I both grew up in the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Squirrel Hill. We went to the same schools [he lived right across the street from Linden Elementary were we first met in Kindergarten], though we didn't routinely hang out [and start a band] together until high school.

We reconnected after my father brought me a copy of Snow Angels he stumbled across in the Faulkner book store in Pirates Alley, New Orleans. Since then, I've been just one in a legion of avid readers of O'Nan's works all over the world.

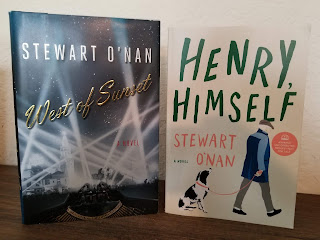

With his new novel Henry, Himself set to publish on April 9, I reached out to Stewart to ask him if he would allow me to exploit our acquaintance by granting me an interview. He foolishly agreed. If you're a fan, I guarantee that you'll not read a Stewart O'Nan interview quite like this one anywhere else.

Eric Sandberg: When Scott Turow writes a new book it's going to be in a courtroom, if it's Kathy Reichs, bones are sure to figure heavily. You are a literary writer with a healthy curiosity and we fans never know what your next book is going to be about: A family tragedy, a crime spree, World War II, fire and plague, a restaurant about to close - I could go on...and on.

Yet with all this variety in your work, you've managed to write three books about the same family. What keeps bringing you back to the Maxwells?

Stewart O'Nan: I guess it's that feeling that I haven't told the whole story. That goes way back to being a short story writer — the amount of compression that goes on. In order to get that compression, you leave a lot out. When I was writing Wish You Were Here I thought the book was going to be all about Emily Maxwell but, as it turned out, I thought the other characters were just as interesting so I followed them as well.

I really didn't get to tell her whole story, so when I started writing Emily Alone I needed to give her some room. And then, just thinking about Henry, he's dead and there's two other books. So we have hearsay about him from the other characters but we don't really know him. I started thinking 'Who exactly was Henry?'

I'm always attracted to a life story. Emily Alone is a life story the same way Henry, Himself is a life story. I figured let's give Henry his room and go back and see what I could find.

Eric: I recently read an essay by the Argentinian novelist César Aira in the Paris Review where he discussed at great length his theories on the "Law of Diminishing Returns" in analyzing the source of his writer's block. I will admit that much of it was over my head, but one section particularly caught my interest as he discussed the necessity of creating all the "circumstantial details" required to flesh out a novel. "Once they are written down," he states, "their necessity becomes apparent", but while inventing them, they seem "childish" and "silly" and fill him with an "invincible despondency" (laughter).

I thought of you, [SO: Thank you.] whose best works are tapestries of circumstantial details that create a whole greater than their parts and, based on Aira's experience, I wonder how you've made it this far without topping yourself.

SO: John Gardner said, in The Art of Fiction, a lot of what's in a novel isn't there because the novelist wants it there, it's because the novelist needs it there. It's like that Laurie Anderson line "You know, I think we should put some mountains here. Otherwise, what are the characters going to fall off of?"

You want to build a world that is your character's world and you want that world to challenge your character — to challenge everything that is dear to that character. But you've got to have that world there otherwise, what is to be lost?

If Henry dying doesn't lose us that good world around him, if we don't see and feel that world, then we'll never feel the loss. We're not losing anything. There are a lot of stories I like to read, and I like to write, which involve character or character consciousness trying to save what is lost — trying to salvage a word that is gone.

Older people, in their seventies and eighties, that's what they're trying to hang on to...or make sense of — both of those things at once. They're trying to hold on to both the good and the bad. But in order to have the good in the bad, you have to have that whole world with all the little stuff, like luggage, a dead deer on the roadside, everything. That's the fun of it. That's the discovery, finding the stuff that you didn't know was there — that you didn't know that you needed — that end up meaning a lot to the characters.

Eric: It sounds like you're the opposite of César Aira, you revel in the circumstantial details.

SO: For particular books I guess that makes sense. For other books maybe it doesn't mean that much. A book like A Prayer For the Dying weighs in at about one hundred and forty manuscript pages, there is a ton of stuff that is left out. It's all action.

I was reading a book called Understanding Comics [by cartoonist Scott McCloud] the other day. It talks about the structure of comics and how, in different cultures, the movement from frame to frame differs. In some cases the next frame will take you to another scene and in others the next frames are different moments within the same scene. I think, in this book, I'm doing that a lot more than moving from scene to scene. I'm hanging on to the scene. I'm doing that close up stuff like in a French film. There are a lot of one person scenes — a lot of scenes with no dialogue.

Eric: In Henry, Himself. Henry is fascinating in his dullness. He has the odd hobby, but the only thing that seems to inspire - and I hesitate to use the word - passion in him is the almost futile need to restore order no matter how mundane the thing that has gone slightly awry - not necessarily with his family, but with stopped up drains, bald patches in the grass and broken garbage disposals.

SO: This goes back to the big question of who is Henry? We're the sum total of all the things we do — that we dream. Henry is very tamped down in a way. He's part of the "Greatest Generation". They're there to be steady, they're there to take care of things and make sure that things work. I think that their passion was in their work.

Their wives were supposed to take care of the home and they were supposed to go out and have a career. By the time that we meet Henry his career is long passed. He can hearken back to it and think about it, but it's pretty much gone.

There is also this lingering effect of his war time experience that keeps him steady and not too excitable about things because nothing is ever going to be as wild and chaotic and maddening as his war experience. When he comes back all he wants is for things to be quiet and peaceful.

I knew your brother and your mother but your father was like Phyllis's husband Lars to me. I never saw him, never met him and if I ever asked about him, my guess is I didn't get a memorable answer. How much of your father have I finally met after reading this book?

SO: Not that much, I think. It's a combination of my father and my grandfather, who plays much more into it, I think. That's the time frame. Also the job — my grandfather worked for Westinghouse. The house where the book takes place is based on the house they lived in on Grafton Street in Highland park.

Eric: When we were lads I don't mind telling you now that I looked up to you quite a bit. Aside from you being several inches taller, you always seemed to be a bit ahead of the curve and you saw things differently than most people. You were the funniest person I knew.

Walking to school with you was often a master class in observational humor. Sometimes it's hard to reconcile that Stew with the often harrowing tales written by the Stewart O'Nan I discovered much later in life.

An acquaintance of mine, a singer-songwriter named Peter Himmelman, writes serious songs of great depth and passion which touch on the human condition, much like your books. But in person, he always has everyone in stitches. Do you have an explanation for this dichotomy, and are you still funny?

SO: It's hard to say if you're funny or not...

Eric: I suppose I should ask Mrs. O'Nan that question.

SO: It's always up to the crowd. At the time we were growing up there was a great irreverence. We were seeing Monty Python on channel 13. This was fresh stuff when we were eleven or twelve years old. I think we were thirteen when when Saturday Night Live debuted. Richard Pryor and George Carlin were probably the funniest men in America. It was a very funny time — the freewheeling late sixties/early seventies, anything goes.

You could poke fun at anything, and probably for good reason. The major institutions in the country had been debunked and seen as morally bankrupt, which is still true today. So I think it was just about getting into that spirit. We were watching [expletive deleted] Laugh In!

My first major influence, if we were to throw out Tarzan, would be the Peanuts comic strips. It's still some of the best American writing I've ever read. It does everything. It has a huge range. It's about jokes but, in a weird way, it's deadly serious about these little kids and what they represent.

At the beginning of my writing I think was more influenced by serious stuff but I was also influenced by Horror and Science Fiction. That's what I read mostly from my teen years up until my early twenties. If my earlier books are a bit more dire that's the influence of the Horror and maybe some of that morbid Science Fiction.

Another big influence was the Horror comics I used to read at the Squirrel Hill Newsstand. Tales of the Unexpected, Creepy, Eerie and, God forbid, Vampirella.

I liked that morbid, mordant sense of humor and the idea that 'you're going to get yours' — that weird sense of macabre poetic justice. Yeah, it's hard to be funny on the page, unless your George Saunders, I guess.

Eric: I've heard you speak at readings about your writing process - boxes and boxes of legal pads, yada, yada, and what you choose to write about seems to be sparked by your own curiosity - and how satisfying that curiosity can lead to a book. West of Sunset, for example: you were doing research for a book about Los Angeles and got caught up in a footnote about F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood. Your curiosity about that led to a very different book.

I recall visiting you at your apartment at Boston University and you played me cassette recordings you had made of late night street interviews you conducted with pimps, prostitutes and drug dealers in the Combat Zone. For someone who was studying Aerospace Engineering at the time, I wonder if that was the germ of the curiosity that led to your ultimate career choice?

SO: It's that documentary curiosity, that wondering about how other people live beyond my own small scope. That's always been there, I think. It also goes back to just reading. Even though I was there to study Aerospace Engineering, I was still reading voraciously because I had a library card there so I would go into the stacks at BU's Mugar library and check out Camus and Flaubert — I was going through a big French phase at that time.

Again, I'm not sure why. I had no big plans for being a writer but, whether it was comic books, Peanuts, Stephen King or Harlan Ellison, I was always a reader. At least that's always been my explanation for how it happened — how I went from being an Aerospace engineer to being a short story writer in my basement after work. I just love to read.

Eric: Finally, I just finished a little light reading, a book called The Sentence Is Death by Anthony Horowitz. One of the red herrings in this murder mystery was that a noted literary writer was secretly the author of a series of trashy, sex-fueled million-selling fantasy novels [laughter]. Her agent defends her, stating "You know the market for literary fiction, Anthony, it's tiny, almost non-existent."

Once again, I thought of you.

SO: That's what they always tell us, but that's where the big fellas come out of. Everyone said Anne Tyler would sell three thousand books her whole career and now she's at the top of the Best Seller list. 'Alice Monroe, you're not going to make any money writing short stories...' Nobel Prize. If it's good it will sell.

Eric: It's not a very well kept secret that you wrote a spy novel under a nom-de-plume [A Good Day To Die, James Coltrane]. It wasn't made into a movie with Matt Damon, or even Mark Wahlberg. Was it hard to resist making it just a tad too literary perhaps?

SO: If I could have sold it as a literary novel I would have but I had too many books piled up at that point. I had three, if not, four books ready to go at that point. I just wanted them off of my desk. That book is basically a twist on For Whom the Bell Tolls. I want to say that City of Secrets is also kind of, too.

Here's that lone figure that is part of a revolution but doesn't know exactly where he stands. Having grown up in the sixties and seventies, and lived through all those weird hijackings and bombings, the SLA, Entebbe, Munich, all that stuff, you think about all the people who got caught up in that. For young people, with no direction it can happen very quickly.

It's always a fascinating one for me. It's like Graham Greene: is this one of his entertainments or is this one of his deadly serious spiritual quest books? Or is it the two of them together? Robert Stone had that same problem. When I was writing City of Secrets I was thinking a lot about that. That apocalyptic strain in pop fiction versus serious fiction versus how it is in actual life.

It's like making movies. It's very stylized. I can see where that author doesn't want to go in that direction —paint the setting, move the characters around. It's not a very flexible business model, I guess.

Eric: You seem to be doing OK.

SO: For me it's always a challenge. What kind of book is this going to be? Is this going to be a 'square' book or is it going to be a funky, weird book? I like the funky, weird books where you pretend it's square but its actually funky and weird. It's a shell game that you play with the whole business. There's a Henry Rollins lyric "Soul in the mainstream is such a labeling dream." You have to appear to be doing one thing when you're actually doing another. It's tricky.

A novel can be anything at all. The question is can you get an audience in the door, with the how? and what will they stand for? And at what point can you close the door behind them so that they can't escape? Something like The Speed Queen and A Prayer For the Dying, which are overtly weird, whereas something like Emily Alone and Henry, Himself appear to be pretty square but are, in fact, very odd. But will the reader sit still for it and, if so, what reader?

That's always the question but, by the time you write 'em, it's too late. You do the best you can, you throw them out there and try to move on to whatever is next. That's always the hardest part — figuring out what's next.

Eric: That segues perfectly to my final question: is there anything new that has peaked your interest that you're getting started on, and can you give us an oblique hint as to what it might be?

SO: I got nuthin'.

Interview by Eric Sandberg

At fifty-eight years young, Stewart O'Nan has seen seventeen of his works of fiction published along with two non-fiction books, one of which is Faithful [with Stephen King] a best-selling bleachers-eye-view of the first championship season for the Boston Red Sox since Babe Ruth was traded. All of this since he, with the full support of his saintly wife, Trudy, abandoned his career as an Aerospace engineer to earn his MFA, ultimately publishing his first collection of short stories In The Walled City [Drew Heinz Literary Prize for Literature] in 1993.

His first novel Snow Angels was adapted as a film and at least two other novels are in pre-production with names like Tom Hanks and Emily Watson being bandied about. Early in his career, Granta named him one of America's best young novelists.

Stewart O'Nan and I both grew up in the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Squirrel Hill. We went to the same schools [he lived right across the street from Linden Elementary were we first met in Kindergarten], though we didn't routinely hang out [and start a band] together until high school.

We reconnected after my father brought me a copy of Snow Angels he stumbled across in the Faulkner book store in Pirates Alley, New Orleans. Since then, I've been just one in a legion of avid readers of O'Nan's works all over the world.

With his new novel Henry, Himself set to publish on April 9, I reached out to Stewart to ask him if he would allow me to exploit our acquaintance by granting me an interview. He foolishly agreed. If you're a fan, I guarantee that you'll not read a Stewart O'Nan interview quite like this one anywhere else.

Eric Sandberg: When Scott Turow writes a new book it's going to be in a courtroom, if it's Kathy Reichs, bones are sure to figure heavily. You are a literary writer with a healthy curiosity and we fans never know what your next book is going to be about: A family tragedy, a crime spree, World War II, fire and plague, a restaurant about to close - I could go on...and on.

Yet with all this variety in your work, you've managed to write three books about the same family. What keeps bringing you back to the Maxwells?

Stewart O'Nan: I guess it's that feeling that I haven't told the whole story. That goes way back to being a short story writer — the amount of compression that goes on. In order to get that compression, you leave a lot out. When I was writing Wish You Were Here I thought the book was going to be all about Emily Maxwell but, as it turned out, I thought the other characters were just as interesting so I followed them as well.

I really didn't get to tell her whole story, so when I started writing Emily Alone I needed to give her some room. And then, just thinking about Henry, he's dead and there's two other books. So we have hearsay about him from the other characters but we don't really know him. I started thinking 'Who exactly was Henry?'

I'm always attracted to a life story. Emily Alone is a life story the same way Henry, Himself is a life story. I figured let's give Henry his room and go back and see what I could find.

Eric: I recently read an essay by the Argentinian novelist César Aira in the Paris Review where he discussed at great length his theories on the "Law of Diminishing Returns" in analyzing the source of his writer's block. I will admit that much of it was over my head, but one section particularly caught my interest as he discussed the necessity of creating all the "circumstantial details" required to flesh out a novel. "Once they are written down," he states, "their necessity becomes apparent", but while inventing them, they seem "childish" and "silly" and fill him with an "invincible despondency" (laughter).

I thought of you, [SO: Thank you.] whose best works are tapestries of circumstantial details that create a whole greater than their parts and, based on Aira's experience, I wonder how you've made it this far without topping yourself.

SO: John Gardner said, in The Art of Fiction, a lot of what's in a novel isn't there because the novelist wants it there, it's because the novelist needs it there. It's like that Laurie Anderson line "You know, I think we should

You want to build a world that is your character's world and you want that world to challenge your character — to challenge everything that is dear to that character. But you've got to have that world there otherwise, what is to be lost?

If Henry dying doesn't lose us that good world around him, if we don't see and feel that world, then we'll never feel the loss. We're not losing anything. There are a lot of stories I like to read, and I like to write, which involve character or character consciousness trying to save what is lost — trying to salvage a word that is gone.

Older people, in their seventies and eighties, that's what they're trying to hang on to...or make sense of — both of those things at once. They're trying to hold on to both the good and the bad. But in order to have the good in the bad, you have to have that whole world with all the little stuff, like luggage, a dead deer on the roadside, everything. That's the fun of it. That's the discovery, finding the stuff that you didn't know was there — that you didn't know that you needed — that end up meaning a lot to the characters.

Eric: It sounds like you're the opposite of César Aira, you revel in the circumstantial details.

SO: For particular books I guess that makes sense. For other books maybe it doesn't mean that much. A book like A Prayer For the Dying weighs in at about one hundred and forty manuscript pages, there is a ton of stuff that is left out. It's all action.

I was reading a book called Understanding Comics [by cartoonist Scott McCloud] the other day. It talks about the structure of comics and how, in different cultures, the movement from frame to frame differs. In some cases the next frame will take you to another scene and in others the next frames are different moments within the same scene. I think, in this book, I'm doing that a lot more than moving from scene to scene. I'm hanging on to the scene. I'm doing that close up stuff like in a French film. There are a lot of one person scenes — a lot of scenes with no dialogue.

Eric: In Henry, Himself. Henry is fascinating in his dullness. He has the odd hobby, but the only thing that seems to inspire - and I hesitate to use the word - passion in him is the almost futile need to restore order no matter how mundane the thing that has gone slightly awry - not necessarily with his family, but with stopped up drains, bald patches in the grass and broken garbage disposals.

SO: This goes back to the big question of who is Henry? We're the sum total of all the things we do — that we dream. Henry is very tamped down in a way. He's part of the "Greatest Generation". They're there to be steady, they're there to take care of things and make sure that things work. I think that their passion was in their work.

Their wives were supposed to take care of the home and they were supposed to go out and have a career. By the time that we meet Henry his career is long passed. He can hearken back to it and think about it, but it's pretty much gone.

There is also this lingering effect of his war time experience that keeps him steady and not too excitable about things because nothing is ever going to be as wild and chaotic and maddening as his war experience. When he comes back all he wants is for things to be quiet and peaceful.

I knew your brother and your mother but your father was like Phyllis's husband Lars to me. I never saw him, never met him and if I ever asked about him, my guess is I didn't get a memorable answer. How much of your father have I finally met after reading this book?

SO: Not that much, I think. It's a combination of my father and my grandfather, who plays much more into it, I think. That's the time frame. Also the job — my grandfather worked for Westinghouse. The house where the book takes place is based on the house they lived in on Grafton Street in Highland park.

Eric: When we were lads I don't mind telling you now that I looked up to you quite a bit. Aside from you being several inches taller, you always seemed to be a bit ahead of the curve and you saw things differently than most people. You were the funniest person I knew.

Walking to school with you was often a master class in observational humor. Sometimes it's hard to reconcile that Stew with the often harrowing tales written by the Stewart O'Nan I discovered much later in life.

An acquaintance of mine, a singer-songwriter named Peter Himmelman, writes serious songs of great depth and passion which touch on the human condition, much like your books. But in person, he always has everyone in stitches. Do you have an explanation for this dichotomy, and are you still funny?

SO: It's hard to say if you're funny or not...

Eric: I suppose I should ask Mrs. O'Nan that question.

SO: It's always up to the crowd. At the time we were growing up there was a great irreverence. We were seeing Monty Python on channel 13. This was fresh stuff when we were eleven or twelve years old. I think we were thirteen when when Saturday Night Live debuted. Richard Pryor and George Carlin were probably the funniest men in America. It was a very funny time — the freewheeling late sixties/early seventies, anything goes.

You could poke fun at anything, and probably for good reason. The major institutions in the country had been debunked and seen as morally bankrupt, which is still true today. So I think it was just about getting into that spirit. We were watching [expletive deleted] Laugh In!

My first major influence, if we were to throw out Tarzan, would be the Peanuts comic strips. It's still some of the best American writing I've ever read. It does everything. It has a huge range. It's about jokes but, in a weird way, it's deadly serious about these little kids and what they represent.

At the beginning of my writing I think was more influenced by serious stuff but I was also influenced by Horror and Science Fiction. That's what I read mostly from my teen years up until my early twenties. If my earlier books are a bit more dire that's the influence of the Horror and maybe some of that morbid Science Fiction.

Another big influence was the Horror comics I used to read at the Squirrel Hill Newsstand. Tales of the Unexpected, Creepy, Eerie and, God forbid, Vampirella.

I liked that morbid, mordant sense of humor and the idea that 'you're going to get yours' — that weird sense of macabre poetic justice. Yeah, it's hard to be funny on the page, unless your George Saunders, I guess.

Eric: I've heard you speak at readings about your writing process - boxes and boxes of legal pads, yada, yada, and what you choose to write about seems to be sparked by your own curiosity - and how satisfying that curiosity can lead to a book. West of Sunset, for example: you were doing research for a book about Los Angeles and got caught up in a footnote about F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood. Your curiosity about that led to a very different book.

I recall visiting you at your apartment at Boston University and you played me cassette recordings you had made of late night street interviews you conducted with pimps, prostitutes and drug dealers in the Combat Zone. For someone who was studying Aerospace Engineering at the time, I wonder if that was the germ of the curiosity that led to your ultimate career choice?

SO: It's that documentary curiosity, that wondering about how other people live beyond my own small scope. That's always been there, I think. It also goes back to just reading. Even though I was there to study Aerospace Engineering, I was still reading voraciously because I had a library card there so I would go into the stacks at BU's Mugar library and check out Camus and Flaubert — I was going through a big French phase at that time.

Again, I'm not sure why. I had no big plans for being a writer but, whether it was comic books, Peanuts, Stephen King or Harlan Ellison, I was always a reader. At least that's always been my explanation for how it happened — how I went from being an Aerospace engineer to being a short story writer in my basement after work. I just love to read.

Eric: Finally, I just finished a little light reading, a book called The Sentence Is Death by Anthony Horowitz. One of the red herrings in this murder mystery was that a noted literary writer was secretly the author of a series of trashy, sex-fueled million-selling fantasy novels [laughter]. Her agent defends her, stating "You know the market for literary fiction, Anthony, it's tiny, almost non-existent."

Once again, I thought of you.

SO: That's what they always tell us, but that's where the big fellas come out of. Everyone said Anne Tyler would sell three thousand books her whole career and now she's at the top of the Best Seller list. 'Alice Monroe, you're not going to make any money writing short stories...' Nobel Prize. If it's good it will sell.

Eric: It's not a very well kept secret that you wrote a spy novel under a nom-de-plume [A Good Day To Die, James Coltrane]. It wasn't made into a movie with Matt Damon, or even Mark Wahlberg. Was it hard to resist making it just a tad too literary perhaps?

SO: If I could have sold it as a literary novel I would have but I had too many books piled up at that point. I had three, if not, four books ready to go at that point. I just wanted them off of my desk. That book is basically a twist on For Whom the Bell Tolls. I want to say that City of Secrets is also kind of, too.

Here's that lone figure that is part of a revolution but doesn't know exactly where he stands. Having grown up in the sixties and seventies, and lived through all those weird hijackings and bombings, the SLA, Entebbe, Munich, all that stuff, you think about all the people who got caught up in that. For young people, with no direction it can happen very quickly.

It's always a fascinating one for me. It's like Graham Greene: is this one of his entertainments or is this one of his deadly serious spiritual quest books? Or is it the two of them together? Robert Stone had that same problem. When I was writing City of Secrets I was thinking a lot about that. That apocalyptic strain in pop fiction versus serious fiction versus how it is in actual life.

It's like making movies. It's very stylized. I can see where that author doesn't want to go in that direction —paint the setting, move the characters around. It's not a very flexible business model, I guess.

Eric: You seem to be doing OK.

SO: For me it's always a challenge. What kind of book is this going to be? Is this going to be a 'square' book or is it going to be a funky, weird book? I like the funky, weird books where you pretend it's square but its actually funky and weird. It's a shell game that you play with the whole business. There's a Henry Rollins lyric "Soul in the mainstream is such a labeling dream." You have to appear to be doing one thing when you're actually doing another. It's tricky.

A novel can be anything at all. The question is can you get an audience in the door, with the how? and what will they stand for? And at what point can you close the door behind them so that they can't escape? Something like The Speed Queen and A Prayer For the Dying, which are overtly weird, whereas something like Emily Alone and Henry, Himself appear to be pretty square but are, in fact, very odd. But will the reader sit still for it and, if so, what reader?

That's always the question but, by the time you write 'em, it's too late. You do the best you can, you throw them out there and try to move on to whatever is next. That's always the hardest part — figuring out what's next.

Eric: That segues perfectly to my final question: is there anything new that has peaked your interest that you're getting started on, and can you give us an oblique hint as to what it might be?

SO: I got nuthin'.

Comments

Post a Comment